Samuel Goodman (1805-1881): “I swapped a pitchfork for a pint jug. But you’ve got to know when to weed, when to water, and when to show them the door.”

Image by Ideogram 3.0 at Abacus.ai, July 2025

This historical account details Samuel Goodman's significant life transition from farming to innkeeping in mid-19th-century Devon. Facing declining agricultural yields and a changing market, Goodman, with the unwavering support of his wife, Harriett, decided to sell their farm in 1860. The text explores the motivations behind this dramatic career shift, highlighting his observations of a local inn and his realisation that his skills could be transferable. It also touches upon Harriett's prior familiarity with pub life through her father, which likely eased their adaptation to their new venture. Ultimately, the narrative celebrates Goodman's success and contentment in his new role, viewing it as a form of "survival" rather than merely diversification. The piece contrasts the demands of farming with those of innkeeping, emphasising how both taught him valuable lessons about reading the world around him.

Listen now to the podcast team at Notebook LM unpack this first chapter in Samuel Goodman’s life story - Goodman's Leap: From Plough to Pint in Devon. (Note: the process for doing this is simple. Upload the text of the story to your account at Notebook LM and generate the podcast.

Note: For more in-depth analysis, try the Briefing feature too.

eg. Briefing Document: "From Plough to Pint: A Life Transformed" - Samuel Goodman (1805-1881)

This briefing document reviews excerpts from "From Plough to Pint: A Life Transformed," the memoir of Samuel Goodman, focusing on his significant career transition from farming to innkeeping in mid-19th-century Devon. The text highlights his motivations, the practicalities of the change, and the character traits that enabled his success.

Now read Chapter 1 of Samuel’s story.

When the Soil Stopped Speaking

They say some men are born to the soil. I used to count myself among them. For twenty years, I walked the fields of Allaleigh with turnips at my feet and sky in my eyes. Twenty-seven acres of Devon clay taught me more than any book ever could—about patience, about sweat, about the fine line between hope and hunger. But around 1858, the land started answering back with silence.

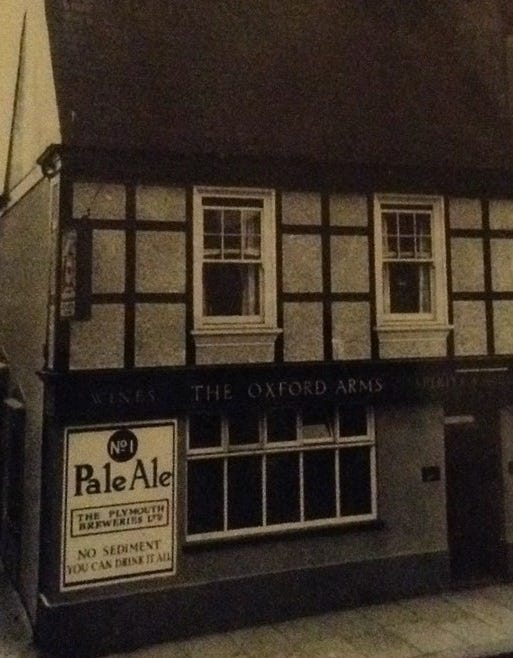

I remember the day I knew I was done. It was market day in Totnes. I’d taken a barrow of leeks and a few barrels of cider—my own pressing, decent stuff. I stopped at The Oxford Arms for a drink before the walk home. The place had a hum to it, like a hive at dusk. Steam rose off stewpots, boots thudded on floorboards, and a boy was tuning a fiddle by the hearth. I watched the innkeeper—a thin fellow with elbows sharper than his welcome—pour drinks with a scowl and chase coin like it owed him a personal debt. That’s when I thought, I could do better than this. And I might have to.

Farming was changing. Yields weren’t what they were, and the market favoured the large holders. I had no sons old enough yet to take a plough, and the soil didn’t warm to tired hands the way it used to. But I still had my wits, my back, and a name folks didn’t spit at.

When I told Harriett I wanted to run an inn, she didn’t flinch. Just raised one eyebrow and said, “Will I have to wear an apron or just be the one who fills the jars?” That was her way—sharp as vinegar, steady as stone. We’d been through enough by then. She married me when she was barely seventeen, and I was twice that. They called it a good match. It was more than that. She grew into the role with a grace that left me proud—and, at times, quietly awed.

So we sold the farm and moved into Totnes. We took up at Number Seven Oxford Lane, with the inn license in my name and the weight of a new life in our hands. I swapped pitchfork for pint jug. Found that people are not so different from land—you tend them right, and most will yield decently. But you’ve got to know when to weed, when to water, and when to show them the door.

Farming taught me how to read clouds. Innkeeping taught me how to read men.

That first year—1860—we scrubbed the place from beam to cellar. Harriett took to the kitchens; I handled the books and barrels. Our children pitched in where they could. And I started learning the rhythm of a house that never slept. Harriett was quite used to life in a pub; her father, Samuel Allery (Ellery), was the publican at The Lord Nelson in Totnes in 1850.

I don’t regret the shift. The land raised me, but the inn carried us forward. Some men chase gold. I chased a warm fire, a full table, and the kind of work that changes with the hour. Diversify, they say now. I just called it survival.

And I was good at it. Still am.

PS: These vignettes are captured from researched facts about the life of Samuel Goodman, who married my great x 3 grandmother Harriett Allery. Their home was in Totnes, Devon, where they raised a family and became innkeepers at the Oxford Arms. The stories are fictionalised and told in the first person and are AI-assisted.

https://www.closedpubs.co.uk/devon/totnes_oxfordarms.html

Harriett’s story forms the first 10 chapters in “Your Story Matters.” You can read these here: